The history of Indo-German relationships is old indeed! German traders, travellers, mercenary soldiers, and seekers of adventures and fortune visited India. According to Walter Leifer, the Carolingians called the entire continent of Asia as India. India remained their land of fascination. A new chapter in the history of an authentic relationship between Germany and India, however, started in Tarangambadi in the Coromandal Coast belonging to the present day Mayilāṭutuṟai District of Tamil Nadu. This small sea port became the meeting point where the Germans and the Tamils of eighteenth and nineteenth centuries began to meet and exchange diverse kinds of knowledge. As a result, reliable first-hand information about the history, language, literature, geography, religions, and socio-cultural traditions of the Tamil people started spreading among the Germans. This essay emphasises a few highlights of the impact of Tamil people in eighteenth century Germany.

July 9, 1706 was significant for the beginning of a new Indo-Tamil relationship. On this day, two young Germans, namely Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg (1682–1719) and Heinrich Plütschau (1676–1752) landed in Tarangambadi which was since 1620 a colony of Danish traders and settlers. After being commissioned by King Friedrich IV of Denmark, these Germans came to Tarangambadi and invited its inhabitants to consider embracing the Lutheran Pietism as an alternate way of their thinking, being and living. They extended the legal agreement about the establishment of Tarangambadi, which King Ragunatha Nayak of Tanjore and Ove Gjedde, a Danish representative, signed together. Its third provision ensured Danish subjects of Tranquebar to practice Lutheranism . The missionaries assumed that all inhabitants of Tranquebar, whether they were Shaivites or Vaishnavites or Tamil Muslims or Tamil Roman Catholics or Europeans, were in fact ‘Danish subjects’. By contrast, the worshippers of Tamil deities understood themselves as subjects of the King of Tanjore; they felt accountable to his representative, namely the Maṇiyakkaran. They and the worshippers of village guardian deities maintained fifty-one temples in fifteen villages of Tarangambadi. The Muslims had their two mosques; the Roman Catholics (both Tamil and European) and the European Lutherans met in their own church buildings for worship and socialisation. The Tamil inhabitants hesitated to participate in the worship services of the European Lutherans in their Zion Church (established in 1701) because they did not accept the Tamils on equal terms.

With the arrival of Ziegenbalg and Plütschau the condescending attitudes of Europeans towards the Tamil changed for the better. Their discovery of the richness of the Tamil language and its literature transformed their opinion towards the Tamil. For example, Ziegenbalg learned the Tamil language from a 70-year old blind Tamil teacher, who willingly conducted his veranda-school and his school children, he translated in 1708 three Tamil ethical works, namely Ulakanīti, Koṉṟaivēntaṉ and Nītiveṇpā .He circulated his translation of these works among his readers in Tarangambadi, Germany and Denmark. In his foreword to Nītiveṇpā he confessed how these works led him to drastically change his opinions about the Tamil. He mentioned that the Germans of his time viewed the Tamil people as those who did not have an organised language or a civil code of life. He invited those ignorant Germans to engage with the contents of the Tamil ethical works and discover how the Tamil people, without the ethical impact of the Bible, excelled in their moral behaviour and civil society.

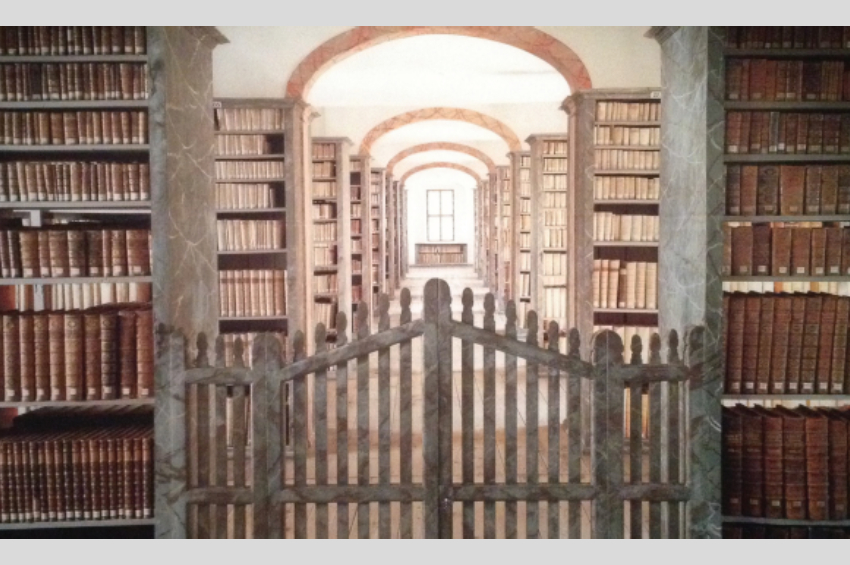

In the same year of 1708, Ziegenbalg compiled a list of 119 Tamil literary works, which the inhabitants of Tranquebar used. He collected their palm leaf manuscripts and established the first public library of India. Information about this Bibliotheca Malabarica (‘Tamil Library’) spread privately in Germany and convinced its readers of the long history of written culture of the Tamil.

Ziegenbalg’s reports about the Tamil, their language, literature and culture appeared in 1708 in Germany and they impressed their readers in Germany, Denmark and England. This report reproduced Tamil vowels, consonants and their combination for ‘r’ and ‘pa’. This was the first time that Ziegenbalg’s German readers got a change to see Tamil fonts.

In 1711, Ziegenbalg complied another treatise on the Tamil understanding of God and its diverse expressions. He carefully gleaned relevant information from various Tamil works and entitled his treatise as Malabarian Heathenism . When I translated it into English in 2006, I entitled it Indian Society. In 1712, Ziegenbalg’s colleague Johann Ernest Gründler compiled the Medicus Malabaricus (‘Tamil Doctor’). This manuscript was lost and found just recently. It contains the first representation of Tamil Siddha Medicine. It invited German medical personnel to engage with Tamil ways of diagnosing and healing sicknesses. On September 6, 2021, the Francke Foundations conducted an online workshop on this manuscript. We need Tamil scholars, with expertise in Tamil Siddha Medicine, to study it.

In 1712, Ziegenbalg and his colleague Johann Ernest Gründler installed the first mechanised printing press in Tranquebar, which they had received as a gift from the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) in London/UK. This press started the democratisation of knowledge among the Tamil; it also led the way to systematize Tamil fonts, printing and publication. While the SPCK provided the press and printing paper, the Lutherans in Halle (Saale) in Germany created the metal fonts and sent typesetters to Tranquebar. The impact of the Tamil language was so significant that Christians in three countries cooperated in introducing mechanised printing among the Tamil.

Ziegenbalg’s most popular treatise in circulation was and still is his Genealogy of the Malabarian Gods (1713). It presents Tamil understandings of both Nirguna- and Saguna Brahman, the manifestation of Brahman as Śiva, Viṣṇu and Brahmā; it also presents the different names of these male deities and their consorts; it also names the festivals that are celebrated in honour of these deities. Its first editor, Wilhelm Germann, corrupted Ziegenbalg’s manuscript by inserting large portions of writings by European Indologists and Indian religious educators. I discovered this manuscript at the Royal Library of Denmark in Copenhagen and published its transcript in 2003 . Two years later I translated it into English . Ziegenbalg and his colleague Gründler invited well-known Tamil scholars in and around the Kingdom of Tanjore for exchanging questions and answers on diverse themes of Tamil life. These two men selected ninety-nine letters and translated them into German. These letters engage not only with Tamil notions of Goddesses, Gods, spirit beings, but also with Tamil practices of elementary and higher education, agriculture, rites of passage and the like. For the first time, these letters allow us to hear the original voices and views of the Tamil people from ordinary life setting. I translated these letters into English; my senior colleague Richard Fox Young at Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey/ USA edited my English text. We published the text in 2013 .

Ziegenbalg’s another most important work is the Grammatica Damulica (1716), the first LatinTamil grammar to be published in Germany. We should note that the proof reader of this grammar was Peter Malaiyappan, a young Tamil man from Tranquebar. He accompanied Ziegenbalg on his journey to Europe. While I translated it from Latin into English, I noticed that it was based on a Portuguese manuscript entitled Arte Tamulica, probably written by the Jesuit Balthazar da Costa (1610–1673), who worked in Karur area in Tamil Nadu. On hearing about my English translation of this grammar, the organisers of the World Classical Tamil Conference in Coimbatore (2010) invited me to present a paper.

Apart from these and similar contributions to Tamil by German Lutheran missionaries, the Halle Reports (1710–1767) consisting of nine large volumes, contain valuable information on the Tamil people, their language, literature, geography, climatic conditions, trade, travel, agriculture and the like. Tamil scholars will treat them as a treasure trove. The multiple contributions of German Lutheran missionaries to Tamil studies, partly documented in C.S. Mohanavelu’s German Tamilology still await further research. In 1996, I identified in the Francke Foundation in Halle (Saale) and the Royal Library in Copenhagen several Tamil palm leaf manuscripts associated with the Lutherans of Tarangambadi. Various writings on Tamil by Christopher Theodosius Walter, Philip Fabricius, Samuel Christopher John, Johann Peter Rottler and others still await research. The Mission Archives at the Francke Foundations in Halle (Saale) keep their manuscripts in excellent condition. I facilitated microfilming of some of these documents. In 2006, when the Lutheran Church celebrated their 300th anniversary in Tamil Nadu, Professor Thomas Müller-Bhalke handed over these microfilm rolls to the Lutheran Heritage Archives at Gurukul Lutheran Theological College & Research Institute in Kellys, Chennai. Students of Tamil Studies will find these microfilm documents as treasure trove of primary source materials.

In 18th century, some Germans showed great interest in learning Tamil. In 1711, Heinrich Plütschau and his Tamil companion Timothy Kudiyān were the first Tamil teachers at the Francke Foundations in Halle (Saale), Germany. Their students included Heinrich Julius Elers (1667–1728), who later printed the Grammatica Damulica and Professor Christian Benedict Michaelis (1680–1764). Tamil was taught in Halle (Saale) until mid-18th century. For example, the famous Christian Friedrich Schwartz (1726–1798), the Rajaguru of Tanjore and caretaker of Prince Serfojee II, learnt Tamil with Benjamin Schultze, who had worked both in Tranquebar and Chennai. The advent of Sanskrit studies in Germany in 19th century caused the eclipse of Tamil studies there. However, a few places continued the tradition of teaching Tamil to Germans and the Tamil Diaspora. The Tamil Department at the University of Cologne is one such place. As I wrote my dissertation for the Higher Doctorate (‘Habilitation’ degree), I had the joy of using their library for three weeks in 2000. There I met Tamil teachers such as Dr. Ulrike Nikolas and Dr. Thomas Malten.

I am indeed grateful to the Honourable Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, M.K. Stalin, for supporting this excellent centre with money (July 2021). As a beneficiary of this centre, I am sure that his support would revive the study of Tamil there both by German and Tamil students in diaspora. Among other places and sources, my research at this Tamil Department in Cologne contributed to my earning the most prestigious degree of Habilierter Doctor Theologiæ (Dr. theol. habil). As a son of the Tamil soil and only Indian, I am grateful to hold this degree from the Faculty of Theology at the Martin Luther University Halle–Wittenberg in Halle (Saale), Germany.